Part of the Ortho NI Group

At Ortho NI Sport, we perform hundreds of procedures every year with consistently high patient satisfaction. With a proven record of effective treatment and recovery management, you can be sure you are in the best of care at Ortho NI Sport.

Introduction

Anatomical Overview

Femero-acetabular Impingement / Labral Tear

Trochanteric Bursitis

Snapping Hip Syndrome

Sports Hernia

Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) Injury

Anterior Knee Pain

Articular cartilage damage

Chondromalacia Patellae

Iliotibial (IT) Band Syndrome

Medial collateral ligament (MCL) Injury

Meniscal tears

Osteochondritis Dessicans

Patella Dislocation

Patella Tendonitis

Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL) Injury

Shoulder Instability

Rotator Cuff Tear

Hip Arthroscopy

Trochanteric Bursa Injection

Sports Hernia Repair

Knee Arthroscopy

ACL Reconstruction

MPFL Reconstruction

Shoulder Arthroscopy

Rotator Cuff Repair

Anatomy

Hip Conditions

Knee Conditions

Shoulder Conditions

Sports Procedures - Hip

Sport Procedures - Knee

Sports Procedures - Shoulder

Our award-winning Ortho NI Sport specialists, Mr Pooler Archbold, Mr Dennis Molloy and Mr Roger Wilson have extensive experience of successfully treating sport-related conditions.

content

Femero-acetabular impingement

Normal Hip Movement

Normal Hip Movement

Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) is a condition where the bones of the hip are abnormally shaped. Because they do not fit together perfectly, the hip bones rub against each other and cause damage to the joint.

Types of FAI

There are three types of FAI: pincer, cam, and combined impingement.

CAM lesion impingement

CAM lesion impingement

CAM Lesion. In CAM impingement the femoral head is not round and cannot rotate smoothly inside the acetabulum. A bump forms on the edge of the femoral head that grinds the cartilage inside the acetabulum.

Pincer lesion impingement

Pincer lesion impingement

Pincer. This type of impingement occurs because extra bone extends out over the normal rim of the acetabulum. The labrum can be crushed under the prominent rim of the acetabulum.

Combined. Combined impingement just means that both the pincer and CAM types are present

Treatment – femero-acetabular impingement

Nonsurgical Treatment

Activity changes. Your doctor may first recommend simply changing your daily routine and avoiding activities that cause symptoms.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications. Drugs like ibuprofen can be provided in a prescription-strength form to help reduce pain and inflammation.

Physical therapy. Specific exercises can improve the range of motion in your hip and strengthen the muscles that support the joint. This can relieve some stress on the injured labrum or cartilage.

Surgical Treatment

If tests show joint damage caused by FAI and your pain is not relieved by nonsurgical treatment, your doctor may recommend surgery.

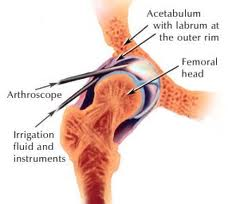

Many FAI problems can be treated with arthroscopic surgery. Arthroscopic procedures are done with small incisions and thin instruments. The surgeon uses a small camera, called an arthroscope, to view inside the hip.

During arthroscopy, your doctor can repair or clean out any damage to the labrum and articular cartilage.

He can correct the FAI by trimming the bony rim of the acetabulum and also shaving down the bump on the femoral head. Some severe cases may require an open operation with a larger incision to accomplish this.

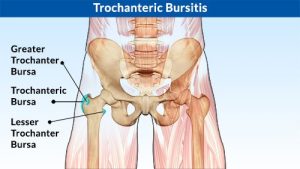

Trochanteric Bursitis (Greater Trochanter pain Syndrome)

Greater trochanteric pain syndrome is also often called trochanteric bursitis.The main symptom is pain over the outside of your upper thigh which can be felt as low as the region of the knee.

Most cases are due to minor injury or inflammation to tissues in your upper, outer thigh area.Commonly the condition goes away on its own over time. Anti-inflammatory painkillers, physiotherapy and steroid injections can all sometimes help.

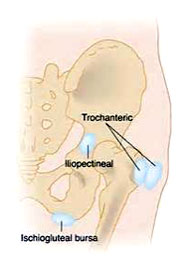

Greater Trochanteric pain Syndrome

Greater trochanteric pain syndrome is a condition that causes pain over the outside of your upper thigh (or thighs). The cause is usually due to inflammation or injury to some of the tissues that lie over the bony prominence (the greater trochanter) at the top of the thigh bone (femur). Tissues that lie over the greater trochanter include muscles, tendons, strong fibrous tissue (fascia), and bursae.

Greater trochanteric pain syndrome used to be called trochanteric bursitis. This was because the pain was thought to be coming from an inflamed bursa that lies over the greater trochanter. A bursa is a small sac filled with fluid which helps to allow smooth movement between two uneven surfaces. There are various bursae in the body and they can become inflamed due to various reasons.

Who Gets Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome

It is a common condition. It is more common in women than in men. It most often occurs in people who are aged over 50 years. However, it can also occur in younger people, especially runners. It is not clear exactly how many people develop this condition. However, one study of 3,026 people aged from 50-79 years found that greater trochanteric pain syndrome was present in nearly 1 in 4 women and nearly 1 in 10 men.

Treatment of Trochanteric Pain Syndrome

Greater trochanteric pain syndrome is usually self-limiting. That is, it usually goes away on its own in time. However, it commonly takes several weeks for the pain to ease.

Symptoms can persist for months, and sometimes longer in a small proportion of cases. However, persistence does not mean that there is a serious underlying condition or that the hip joint is being damaged.

To try and speed up the healing process a number of interventions are useful and may be recommended:

- The use of topical heat and ice to the painful area – 1min/1min alternate for 30 mins every evening

- Regular use of NSAIDS

- Ultrasound guided injection of steroid to the bursa and surrounding area

- Pilates and core stability exercises (physio)

Snapping Hip Syndrome

The occasional “snapping” that can be heard when walking or moving your leg results from the movement of a muscle or tendon (the tough, fibrous tissue that connects muscle to bone) over a bony structure. In the hip, the most common site is at the outer side where a band of connective tissue (the iliotibial band) passes over the broad, flat portion of the thighbone known as the greater trochanter. The snapping can also occur from the back-and-forth motion that takes place when the tendon, running from the inside of the thighbone (femur) up through the pelvis, shifts across the head of the femur. A tear in the cartilage or some bone debris in the hip joint can also cause a snapping or clicking sensation.

Investigation

A detailed history and examination can provide your physician with most of the information to make a diagnosis of snapping hip syndrome. This can be confirmed with specific investigations

An ultrasound of the effected area can show thickening of the overlying tissues in this condition. Magnetic Resonance Scanning (MRI) can confirm the diagnosis of snapping hip syndrome

Treatment

The vast majority of cases can be treated effectively by physiotherapy, involving stretching of the effected soft tissue, strengthening and alignment treatment. Sometimes, treatment with a corticosteroid injection to the area can relieve inflammation.

Sports Hernia (Athletic Pubalgia)

A sports hernia is a painful, soft tissue injury that occurs in the groin area. It most often occurs during sports that require sudden changes of direction or intense twisting movements.

Although a sports hernia may lead to a traditional, abdominal hernia, it is a different injury. A sports hernia is a strain or tear of any soft tissue (muscle, tendon, ligament) in the lower abdomen or groin area.

Because different tissues may be affected and a traditional hernia may not exist, the medical community prefers the term “athletic pubalgia” to refer to this type of injury. The general public and media are more familiar with “sports hernia,” however, and this term will be used for the remainder of this article.

Anatomy

The soft tissues most frequently affected by sports hernia are the oblique muscles in the lower abdomen. Especially vulnerable are the tendons that attach the oblique muscles to the pubic bone. In many cases of sports hernia, the tendons that attach the thigh muscles to the pubic bone (adductors) are also stretched or torn.

Cause

Sports activities that involve planting the feet and twisting with maximum exertion can cause a tear in the soft tissue of the lower abdomen or groin.

Sports hernias occur mainly in vigorous sports such as ice hockey, soccer, wrestling, and football.

A sports hernia will usually cause severe pain in the groin area at the time of the injury. The pain typically gets better with rest, but comes back when you return to sports activity, especially with twisting movements.

A sports hernia does not cause a visible bulge in the groin, like the more common, inguinal hernia does. Over time, a sports hernia may lead to an inguinal hernia, and abdominal organs may press against the weakened soft tissues to form a visible bulge.

Without treatment, this injury can result in chronic, disabling pain that prevents you from resuming sports activities.

During your first appointment, your doctor will talk to you about your symptoms and how the injury occurred. If you have a sports hernia, when your doctor does a physical examination, he or she will likely find tenderness in the groin or above the pubis. Although a sports hernia may be associated with a traditional, inguinal hernia, in most cases, no hernia can be found by the doctor during a physical examination.

Physical Tests

To help determine whether you have a sports hernia, your doctor will likely ask you to do a sit-up or flex your trunk against resistance. If you have a sports hernia, these tests will be painful.

Imaging Tests

After your doctor completes a thorough exam, he or she may order xrays or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans to help determine whether you have a sports hernia. Occasionally, bone scans or other tests are recommended to rule out other possible causes of the pain.

Nonsurgical Treatment

Rest. In the first 7 to10 days after the injury, treatment with rest and ice can be helpful. If you have a bulge in the groin, compression or a wrap may help relieve painful symptoms.

Physical therapy. Two weeks after your injury, you may begin to do physical therapy exercises to improve strength and flexibility in your abdominal and inner thigh muscles.

Anti-inflammatory medications. Your doctor may recommend non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medicines (ibuprofen or naproxen) to reduce swelling and pain. If your symptoms persist over a prolonged period, your doctor may suggest a cortisone injection, which is a very effective steroid anti-inflammatory medicine.

In many cases, 4 to 6 weeks of physical therapy will resolve any pain and allow an athlete to return to sports. If, however, the pain comes back when you resume sports activities, you may need to consider surgery to repair the torn tissues.

Surgical Treatment

Surgical procedure. Surgery to repair the torn tissues in the groin can be done as a traditional, open procedure with one long incision, or as an endoscopic procedure. In an endoscopy, the surgeon makes smaller skin incisions and uses a small camera, called an endoscope, to see inside the abdomen.

The end results of traditional and endoscopic procedures are the same.

Some cases of sports hernia require cutting of a small nerve in the groin (inguinal nerve) during the surgery to relieve the patient’s pain. This procedure is called an inquinal neurectomy.

Your doctor will discuss the surgical procedures that best meets your needs.

Surgical rehabilitation. Your doctor will develop a rehabilitation plan to help you regain strength and endurance. Most athletes are able to return to sports 6 to 12 weeks after surgery.

Surgical outcomes. More than 90% of patients who go through nonsurgical treatment and then surgery are able to return to sports activity. In some patients the tissues will tear again during sports and the surgical repair will need to be repeated.

Additional surgery. In some cases of sports hernia, pain in the inner thigh continues after surgery. An additional surgery, called adductor tenotomy, may be recommended to address this pain. In this procedure, the tendon that attaches the inner thigh muscles to the pubis is cut. The tendon will heal at a greater length, releasing tension and giving the patient a greater range of motion.

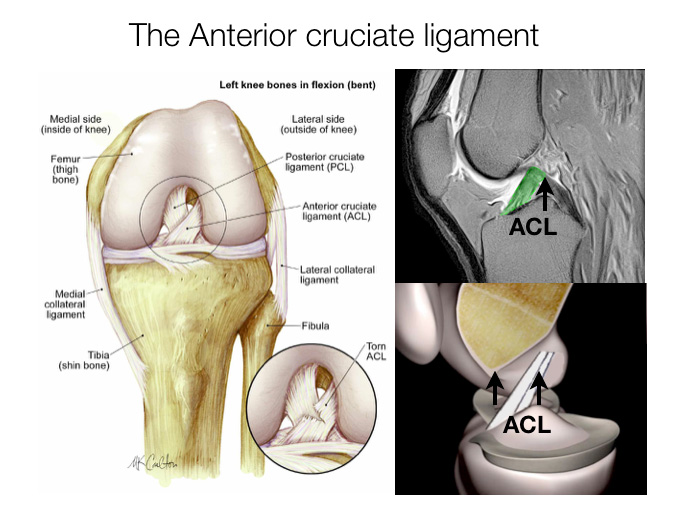

Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) Injury

Also known as ACL tear, ACL rupture, The ACL is one of the main stabilising ligaments of the knee. It runs through the centre of the knee from the back of the thigh bone (femur) to the front of the shin bone (tibia). The ACL prevents excessive anterior translation and rotation of the tibia.

This action is critical to the stability of the knee whilst sidestepping, or pivoting therefore when the ACL is ruptured or torn the tibia moves abnormally such that the knee buckles or gives way.

Mechanism of injury

The ACL is typically injured in a non-contact twisting movement involving rapid deceleration on the leg or a sudden changing of direction such as side stepping, or pivoting. The ACL can also be injured by a direct blow to the knee or by hyperextension.

Symptoms

When you tear your ACL, you typically hear a popping noise and feel your knee give way.

Other typical symptoms include:

- Pain with swelling. Immediate swelling in the knee due to bleeding from the torn ligament. If ignored, the swelling and pain may resolve on its own. However, if you attempt to return to sports, your knee is usually unstable and you risk causing further damage to the cartilage (meniscal tear) of your knee.

- Loss of full range of motion

- Tenderness along the joint line – this is due to bruising of the bone and possible damage to the cartilages of the knee (meniscal tear).

Investigation

X-rays of the knee are usually normal therefore if there is a suspicion of an ACL tear the investigation of choice is a MRI.

Treatment

After an ACL injury your knee is swollen and will stiffen up over 48 hours. Following this your knee enters what is referred to as ‘the inflammatory phase’. If the ACL is reconstructed during this phase there is an increased risk of arthrofibrosis (scarring and post-operative stiffness).

Initial treatment therefore concentrates on minimising swelling and restoring a full and pain free range of movement. This often takes about 6 weeks.

Initial management

- Rest, ice, painkillers and anti-inflammatory medication

- Physiotherapy

Some low demand patients following physiotherapy and lifestyle modifications will have no instability of their knee. In this group of patients non-operative management is indicated.

In higher demand patients or professional athletes (particularly if you wish to return activity such as jumping, cutting, side-to-side sports, heavy manual labor) or those who have frequent buckling episodes an ACL reconstruction is indicated.

Arthroscopic ACL reconstruction

Reconstruction of the ACL is done arthroscopically (key-hole) and involves replacing the torn ACL with a graft. This is usually taken from the hamstring tendons.

The aim of surgery is to prevent the repeated episodes of giving way of the knee. Published results indicate that approximately 90% of patients consider their knee to function normally or nearly normally after surgery. Full contact sport is allowed after 9 months of rehabilitation but not everyone gets back to their previous level of sport. Other problems such as joint surface damage or meniscal tears may co-exist which can interfere with the joints ability to tolerate the high loads associated with sport.

Anterior Knee Pain

Also known as Patellofemoral pain, Anterior Knee Pain is a symptom not a diagnosis. The term simply means ‘pain at the front of the knee’. Anterior knee pain is one of the most common of knee complaints.

Symptoms

A dull, aching discomfort localised around or behind the kneecap. The pain is aggravated by activity, typically comes on at the onset of running, and cycling it may disappear as one ‘warms up” but returns after the activity. It is worse on stairs, prolonged sitting, kneeling and squatting. It may be associated with

- Crepitus, clicking

- Swelling

Investigation

A thorough history and clinical evaluation is important to define the cause.

The investigation of choice is a MRI scan. It is useful in defining the cause of anterior knee pain. However often its findings correlate poorly to the degree of symptoms.

Common Causes

Patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS)

The cause of pain is not clearly understood and is multi-factorial. Numerous factors have been proposed including limb mal-alignment, muscle weakness, patella mal-tracking. It is common in adolescents and young adults, but it can occur at any age, specifically those who are physically active and exercise regularly.

Patellofemoral Arthritis

A form of knee osteoarthritis common among those in middle and older age.

Bursitis

Perpatellar bursitis (housemaid’s knee) – inflammation of a bursa (a small sac of tissue) in the knee.

Infrapatellar bursitis (parson’s knee) – inflammation below the patella.

Patellar Tendinopathy

Otherwise known as jumper’s knee, this is a common and painful overuse disorder.

Osgood-Schlatter Disease

Painful condition common in physically active adolescents and children. It affects the upper shin. It is aggravated by jumping and kneeling along with sporting activities. It is not serious and tends to go away with time.

Chrondromalacia Patella

It is due to softening and degeneration of the cartilage on the patella or to the cartilage on the lower end of the femur on which it slides.

Patellar Mal-alignment

Mal-alignment of the patellar often paired with damage to the cartilage behind the patella.

Bipartite Patella

Common in adolescence, often comes with pain and tenderness. It is usually without symptoms but can vary in severity and may somtimes need surgical treatment.

Treatment

Most cases of anterior knee pain are self-limiting and the treatment is primarily non-surgical. Treatment should be directed towards the cause of the pain.

Non-operative management

- Education – Explanation of the benign nature of the many conditions that cause anterior knee pain. For instance the natural history of Patellofemoral pain syndrome is for the symptoms to resolve after 6 months with an appropriate rehabilitation program.

- Physiotherapy – quadriceps, core strengthening and stretching exercises – restoration of good quadriceps strength and function is an important factor in achieving good recovery

- Modification of activity and maintain proper weight

- Painkillers and anti-inflammatories – mild/ moderate pain killers and anti-inflammatory medications may be taken to provide symptomatic relief.

- Patella strapping

- Foot orthoses

Surgery is rarely indicated.

Articular cartilage damage

Also known as Cartilage injury, the articular cartilage is the smooth white shiny layer of tissue that is a few millimeters thick. It covers the surfaces of the ends of the bones inside the joint. Articular cartilage has the lowest coefficient of friction of any substance known to man, and its function is to make the bone surfaces in the joint smooth and slippery, to allow the joint to move freely.

Articular cartilage damage is a spectrum of injury from single, localised defects to advanced degenerative disease of articular cartilage (knee osteoarthritis).

The cells in articular cartilage are not very metabolically active, and as they have no blood supply they get their oxygen and their nutrition by diffusion from the joint fluid (synovial fluid) in the knee. The relevance of all this is that articular cartilage has very little self-healing potential, and therefore once it is damaged or worn, it tends not to be able to heal up or repair itself on its own.

Mechanism of Injury

Injury to the articular cartilage may be caused by acute trauma (direct blow or instability secondary to ligament injury during sport), chronic repetitive over load or occur spontaneously (osteochondritis dessicans).

Symptoms

These are variable but most frequently presents with localised pain at the site of injury. It may be associated with

- Swelling

- Stiffness

- Catching/crepitus (unstable cartilage flaps)

Investigation

Xrays are used to rule out osteoarthritis and check the alignment of leg. MRI is the best investigation to localise the size and location of the articular cartilage injury.

Treatment

If the symptoms are mild a course of non-operative management will be undertaken. This will include a trial of

- Rest

- Weight loss

- Physiotherapy

- Painkillers and anti-inflammatories – mild/ moderate pain killers and anti-inflammatory medications may be taken to provide symptomatic relief.

Surgery

Surgery is indicated following the failure of non-operative management. Treatment is individualised dependent on patient age, skeletal maturity, low vs high demand activities, the ability to tolerate extended rehabilitation and the size of cartilage injury.

- Arthroscopic debridement and removal of loose bodies

- Fixation of unstable fragments

- Marrow stimulation techniques – Microfracture

- Osteoarticular transfer

- Realignment procedures – High tibial osteotomy

- Partial or Total knee replacement

Chondromalacia Patellae

The word “chondromalacia” means “cartilage softness”. Chondromalacia patellae is a common cause of anterior knee pain. It is due to softening and degeneration of the cartilage on the knee-cap (patella) or to the cartilage on the lower end of the femur on which it slides (femoral trochlea).

A number of factors contribute to the development of chondromalacia patellae these include overuse, previous trauma and anatomical/genetic predisposition.

There is no evidence that chondromalacia patellae progresses to patella-femoral arthritis, which is probably a different entity. In contrast to osteoarthritis, where initial changes to the cartilage occur on the surface, the changes in chondromalacia patellae commence in the deeper layers of cartilage and involve the surface layer later in the development of the condition.

Symptoms

A dull, aching discomfort localised around or behind the kneecap. The pain is aggravated by activity (running, jumping, climbing or descending stairs) or by prolonged sitting. Other symptoms that may feature are a sensation of catching or giving way, crepitation, and swelling of the knee.

Investigation

The investigation of choice is an MRI scan. It is useful to rule out other causes of anterior knee pain and to confirm the extent of the cartilage damage. However its findings correlate poorly to the degree of symptoms.

Treatment

Most cases of chondromalacia patellae are self-limiting and the treatment is primarily non-surgical.

- Physiotherapy- quadriceps strengthening and stretching exercises – restoration of good quadriceps strength and function is an important factor in achieving good recovery

- Modification of activity and maintain proper weight

- Painkillers and anti-inflammatories – mild/ moderate pain killers and anti-inflammatory medications may be taken to provide symptomatic relief.

- Patella strapping

- Foot orthoses

- Injections – can give short-term benefit

Surgery is rarely indicated. In those patients who have a localised cartilage flap that catches when the knee moves, there may be an indication for surgery. However the results from surgery are variable.

Iliotibial (IT) Band Syndrome

Also known as IT band Friction Syndrome, The IT band is a sheet of tissue that runs down the outer side of the leg, from above the hip down to just below the outer side of the knee.

In runners, cyclists or other people who exercise a lot, the IT band is repetitively shifted forward and backwards across the lateral side of the knee causing friction, inflammation and pain. This is called ‘IT Band Syndrome’.

Symptoms

Activity related pain localized to the outside of the knee. The pain typically eases with rest.

Diagnosis

The investigation of choice to confirm IT band syndrome is an MRI scan. This will also rule out associated soft-tissue pathology in the same region (e.g., lateral meniscal tear, LCL sprain/tear, etc)

Treatment

Non-operative management is indicated as the first line of treatment for IT Band syndrome. Physiotherapy and training modifications are the mainstay of treatment and are usually sufficient to resolve the symptoms.

Conservative Management

- Rest and avoid whatever specific activities provoke the symptoms. Training modifications changing shoe wear every 300-500 miles

- Physiotherapy: Stretching IT band (foam roller), Abductor strengthening, deep friction massage

- Steroid/cortisone injection: indicated for failed physiotherapy

Surgery

If conservative management fails and symptoms continue for longer than 6 months a surgical IT band release (a day case operation) may be indicated –the post-operative rehabilitation takes around 3 months prior to a return to heavy activity.

Medial collateral ligament (MCL) Injury

The MCL, also known as: MCL tear, MCL rupture is one of the main stabilising ligaments of the knee. It passes down the inside of the knee from the end of the thigh bone (femur) to the top of the shin bone (tibia). The MCL prevents excessive sideways opening of the knee joint.

This action is critical to the stability of the knee whilst sidestepping.

Mechanism of injury

A MCL injury occurs when the knee is bent inwards towards the other knee stretching and then tearing the ligament.

Injury to the MCL is divided into three grades of severity.

- Grade 1 – the ligament is stretched with small tears within it.

- This is able to keep the knee stable.

- Grade 2 – the ligament is stretched so that it becomes slightly loose.

- This is called a partial tear

- Grade 3 – the ligament is completely torn.

- There is a risk that other ligament damage has occurred.

- The knee is unstable

Symptoms

When you tear your MCL, you typically have pain over the ligament on the inside of the knee.

Other typical symptoms include:

- Swelling – localised swelling on the inside of the knee.

- Bruising

- Instability – Grade 2 and 3 injuries

Investigation

X-rays of the knee are usually normal therefore if there is a suspicion of an MCL tear the investigation of choice is a MRI.

Treatment

The MCL is a ligament that can heal itself in the right circumstances. Most MCL injuries are Grade I. Braces are used for Grade II injuries. Surgery is only occasionally indicated in Grade III injuries that fail to heal with conservative management (12 weeks) or in multi-ligament knee injuries.

Initial management

- Rest, ice, painkillers and anti-inflammatory medication

- Physiotherapy – Physiotherapy should be used in all grades of injury to help relieve the pain and keep the knee moving.

- Bracing- Prevents the knee from being moved sideways, while allowing a knee to flex and extend. This allows the MCL to heal in the position of function whilst preventing stiffness.

Return to play

Return to play follows healing of the ligament and a focused physiotherapy program that includes a graduated strengthening program, core stability and upper body conditioning, a plyometric program and sports specific exercises.

- Grade 1 – return to play 2-4 weeks

- Grade 2 – return to play 6-8 weeks

- Grade 3 – return to play 8-12 weeks

For a surgically managed MCL or multi-ligament injuries full contact sport is allowed after 9 months of rehabilitation but not everyone gets back to their previous level of sport. Other problems such as joint surface damage or meniscal tears may co-exist which can interfere with the joints ability to tolerate the high loads associated with sport.

Meniscal tears

Also known as: cartilage tears, the menisci are two C-shaped shock absorbers that lie within the knee between the femur (thigh bone) and the tibia (shin bone).

They function to optimise force transmission across the knee joint, stabilise the knee and to provide proprioceptive feedback.

The medial meniscus is on the inner side of the knee and the lateral meniscus is on the outer side.

Meniscal tears are common. There are two types of tear:

- Traumatic tears: These result from a sudden high load being applied to the knee. They to occur from twisting on a loaded knee, e.g. rugby side step, football tackles, slips or ski accidents.

- Degenerate tears: As you get older, the menisci become progressively weaker, and are more prone to tear. Around half of meniscal tears in patients over the age of 45 occur spontaneously without a history of an injury.

Symptoms

A meniscal tear causes

- Pain on the inside or outside of the knee.

- Mechanical symptoms such as clicking, catching and locking can be caused by displaced tears.

- Delayed or intermittent knee swelling.

Investigation

The investigation of choice to confirm a tear is an MRI scan. However if you are over the age of 40 or if your surgeon suspects that you may have some associated arthritis in your knee X-rays of your knee will also be requested.

Treatment

Non-operative management is indicated as the first line of treatment for degenerate tears when the symptoms are mild and if there is no significant functional impairment or mechanical symptoms. Surgery is not be indicated if you have significant co-existent osteoarthritis within your knee.

- Rest, Painkillers and anti-inflammatory medication

- Physiotherapy – keeps your knee strong and flexible and reduces pain.Surgery may be required if a meniscal tear is causing significant symptoms, functional impairment or if your knee is locked or won’t fully straighten. If you’re in this category then you need an MRI scan as soon as possible.

- Arthroscopic Menisectomy or Meniscal repair – Surgery for a meniscal tear is done arthroscopically (key-hole). At the time of surgery the tear is typically resected or if it meets certain criteria (a recent peripheral tear, a younger age or a combined ACL reconstruction) it may be repaired.

The goal of the surgery is to relieve pain and improve function. This will require physiotherapy in addition to the surgery.

Osteochondritis Dessicans

Osteochondritis Dissecans (OCD), also known as: OCD lesion is a disorder that tends to occur in younger people (children and young adults). It is where a piece of bone (osteo) plus the overlying articular cartilage (chondral) becomes partially or completely detached from the joint surface.

The typical evolution of OCD is:

Grade 1: Softening of the cartilage with an intact joint surface

Grade 2: Early articular cartilage separation

Grade 3: Partial detachment of the cartilage

Grade 4: Complete separation with loose bodies in the knee

Cause

It most commonly occurs in the knee. The exact cause of OCD is not known. However it is likely that it is caused by repetitive microtrauma, or by interruption to the blood supply of the cartilage and underlying bone.

Symptoms

Activity related pain that is poorly localised. It may be associated with

- Swelling

- Stiffness

- Catching/crepitus (unstable OCD fragments)

Investigation

Xrays are useful and can diagnose the OCD lesion. MRI is the best investigation to characterise the size and location of the lesion, the status of the joint and the presence of loose bodies.

Treatment

The outcome of OCD is correlated to the age that it presents. A younger age correlates with a better prognosis. Open growth plates are the best predictor of successful non-operative management.

If the symptoms are mild and the OCD lesion is stable and not detached from the joint surface a course of non-operative management will be undertaken. This will include a trial of

- Restricted weight bearing and bracing

- Painkillers and anti-inflammatories – mild/ moderate pain killers and anti-inflammatory medications may be taken to provide symptomatic relief.

Surgery

Surgery is indicated following the failure of non-operative management. Treatment is individualised and dependent on patient age, skeletal maturity, and the integrity of the of OCD lesion.

- Arthroscopic drilling

- Fixation of unstable fragments

- Arthroscopic debridement and marrow stimulation techniques

Patella Dislocation

Also known as Episodic patella dislocation, this condition is defined as a history of one or more dislocations of the patella. There is normally an initial traumatic event, non-contact twisting injury or a direct blow.

In over 90% of patients who suffer a dislocation of the patella there is an abnormality in the shape of the groove that the knee cap runs in.

If the patella ‘pops out’ (to the outer/lateral side of the knee) fully, then this is called a ‘patellar dislocation’. If it pops out only partially, this is called a ‘subluxation’.

Often, a patellar dislocation may reduce itself back into place spontaneously. Otherwise the kneecap may need to be manipulated back into place under ‘gas and air’, either by ambulance crew or potentially in an A&E Department.

After a patellar dislocation, the tissues around the inner side of the knee that help hold the patella in place (medial patellofemoral ligament) are torn. If it is a first time dislocation you will be treated in a splint to allow this to heal and scar. However in 50% of case it does not heal properly leaving residual ‘weakness’ and risk of further dislocation.

The more times a patellar dislocates, the more likely it is that there will be repeat episodes of further dislocation

Symptoms

If you have had a patella dislocation your knee will be acutely swollen and painful and you may complain of a feeling of continued instability.

Investigation

Following a dislocation Xrays are required to rule out a fracture or loose body and to make sure that the patella is back in joint.

The investigation of choice is a MRI scan which helps rule out subtle damage of the joint surface (articular cartilage).

Treatment

If you dislocate your patella for the first time without any loose bodies or joint damage a trial of non-operative management should be undertaken.

Non-operative management

- Short-term immobilization – brace for 2-4 weeks to allow the soft tissues on the inside of the knee to heal.

- Physiotherapy – quadriceps, core strengthening and stretching exercises – restoration of good quadriceps strength and function is an important factor in achieving stability.

- Painkillers and anti-inflammatories – mild/ moderate pain killers and anti-inflammatory medications may be taken to provide symptomatic relief following a patella dislocation.

- Patella brace.

If you have 2 or more dislocations then surgery may be indicated to stabilize the knee cap and prevent damage to the joint surface.

Surgery

- Arthroscopic (key-hole) debridement

If there is damage to the surface of the knee joint following a dislocation then key hole surgery may be required to tidy this up. - Medial Patellofemoral Ligament (MPFL) Reconstruction

For recurrent instability reconstruction of the ligament on the inside of the knee that becomes stretched following a dislocation may be required - Surgical realignment

If you have a significant abnormality in the shape of the groove or in the alignment of the patella surgery to correct the alignment of the joint may be required

Patella Tendonitis

Also known as: Jumper’s knee, Patella Tendonitis is an activity related anterior knee pain with patella tendon tenderness.

It is due to micro-tears of the patellar tendon typically a result of repetitive activity such as high intensity training, running, jumping and kicking, all of which place continuous stress on the patellar tendon.

This overuse causes very small tears in the tendon leading to inflammation and pain.

Symptoms

Gradual onset of pain and/or swelling below the kneecap

- Initially the pain occurs following activity and it is more noticeable when going up and down stairs.

- Later the pain occurs during activity or whilst sitting

Investigation

Ultrasound and MRI show thickening of the tendon.

Treatment

Initial treatment should include

- Rest for 2-4 weeks.

- Apply ice for 15-20 minutes, 3-4 times a day for 2-3 days

- Anti-inflammatories may relieve pain and reduce inflammation.

- Physiotherapy – stretching of quadriceps and hamstrings, eccentric exercise program

- Activity modification on your return to exercise. Cross-train in activities that do not place undue stress on the knees (swimming, flexibility/range of motion exercises)

Depending on the severity of the condition, recovery could last from 2 weeks to several months.

Operative intervention is rarely indicated and is only considered following 6 months of failed non-operative management

Surgery

- Surgical excision and suture repair – return to activity in 80-90% of athletes however there may be activity related pain for 4-6 months post surgery

Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL) Injury

Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL) Injury, is also known as PCL tear or PCL rupture. The PCL is one of the main stabilising ligaments of the knee. It runs through the centre of the knee from the back of the shin bone (tibia) to the front of the thigh bone (femur). The PCL prevents excessive posterior translation of the tibia.

Mechanism of injury

The PCL is stronger than the ACL. It requires a more powerful force to tear it and it is therefore a less common knee injury.

The PCL is typically injured when there is impact to the front of the shin pushing the tibia directly backwards (dashboard injury). A PCL tear can also occur from hyperextension injuries or from rapid forced flexion injuries (eg falling and landing on a deeply bent knee).

Symptoms

PCL tears cause pain and some swelling, but this tends to be less severe and obvious than that seen with an ACL tear. Typically people don’t realise that they’ve sustained what is actually a significant injury in the knee and the injury can be missed for a number of weeks.

Investigation

X-rays of the knee are usually normal therefore if there is a suspicion of a PCL tear the investigation of choice is a MRI.

Treatment

If you have suffered an isolated PCL tear a course of non-surgical management is often undertaken.

Initial management

- Rest, ice, painkillers and anti-inflammatory medication

- Physiotherapy – strengthening of the quadriceps muscle is the key factor in successful recovery

- Immobilisation – a 12 week period of brace immobilisation may be recommended in complete PCL tears. These braces push the tibia forward to allow the PCL to heal in the correct position.

If the knee is functionally unstable despite 6 months of appropriate physiotherapy or if the PCL is part of a multi-ligament knee injury, then surgical reconstruction may be indicated.

Shoulder Instability

The shoulder is the most moveable joint in your body. It helps you to lift your arm, to rotate it, and to reach up over your head. It is able to turn in many directions. This greater range of motion, however, can cause instability.

Shoulder instability occurs when the head of the upper arm bone is forced out of the shoulder socket. This can happen as a result of a sudden injury or from overuse.

Once a shoulder has dislocated, it is vulnerable to repeat episodes. When the shoulder is loose and slips out of place repeatedly, it is called chronic shoulder instability.

Anatomy

Normal shoulder anatomy

Your shoulder is made up of three bones: your upper arm bone (humerus), your shoulder blade (scapula), and your collarbone (clavicle).

The head, or ball, of your upper arm bone fits into a shallow socket in your shoulder blade. This socket is called the glenoid. Strong connective tissue, called the shoulder capsule, is the ligament system of the shoulder and keeps the head of the upper arm bone centered in the glenoid socket. This tissue covers the shoulder joint and attaches the upper end of the arm bone to the shoulder blade.

Your shoulder also relies on strong tendons and muscles to keep your shoulder stable.

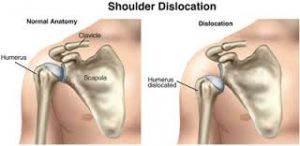

Description

Shoulder dislocations can be partial, with the ball of the upper arm coming just partially out of the socket. This is called a subluxation. A complete dislocation means the ball comes all the way out of the socket.

Left: Normal shoulder stability. Right: Head of the humerus dislocated to the front of the shoulder.

Once the ligaments, tendons, and muscles around the shoulder become loose or torn, dislocations can occur repeatedly. Chronic shoulder instability is the persistent inability of these tissues to keep the arm centered in the shoulder socket.

Shoulder Dislocation

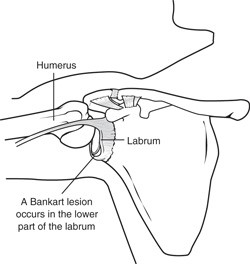

Severe injury, or trauma, is often the cause of an initial shoulder dislocation. When the head of the humerus dislocates, the socket bone (glenoid) and the ligaments in the front of the shoulder are often injured. The labrum — the cartilage rim around the edge of the glenoid — may also tear. This is commonly called a Bankart lesion. A severe first dislocation can lead to continued dislocations, giving out, or a feeling of instability.

Repetitive Strain

Some people with shoulder instability have never had a dislocation. Most of these patients have looser ligaments in their shoulders. This increased looseness is sometimes just their normal anatomy. Sometimes, it is the result of repetitive overhead motion.

Swimming, tennis, and volleyball are among the sports requiring repetitive overhead motion that can stretch out the shoulder ligaments. Many jobs also require repetitive overhead work.

Looser ligaments can make it hard to maintain shoulder stability. Repetitive or stressful activities can challenge a weakened shoulder. This can result in a painful, unstable shoulder.

Multidirectional Instability

In a small minority of patients, the shoulder can become unstable without a history of injury or repetitive strain. In such patients, the shoulder may feel loose or dislocate in multiple directions, meaning the ball may dislocate out the front, out the back, or out the bottom of the shoulder. This is called multidirectional instability. These patients have naturally loose ligaments throughout the body and may be “double-jointed.”

Symptoms

Common symptoms of chronic shoulder instability include:

- Pain caused by shoulder injury

- Repeated shoulder dislocations

- Repeated instances of the shoulder giving out

- A persistent sensation of the shoulder feeling loose, slipping in and out of the joint, or just “hanging there”

Doctor Examination

Physical Examination and Patient History

After discussing your symptoms and medical history, your doctor will examine your shoulder. Specific tests help your doctor assess instability in your shoulder. Your doctor may also test for general looseness in your ligaments. For example, you may be asked to try to touch your thumb to the underside of your forearm.

Imaging Tests

Your doctor may order imaging tests to help confirm your diagnosis and identify any other problems.

X-rays. These pictures will show any injuries to the bones that make up your shoulder joint.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). This provides detailed images of soft tissues. It may help your doctor identify injuries to the ligaments and tendons surrounding your shoulder joint.

Treatment

Chronic shoulder instability is often first treated with nonsurgical options. If these options do not relieve the pain and instability, surgery may be needed.

Nonsurgical Treatment

Your doctor will develop a treatment plan to relieve your symptoms. It often takes several months of nonsurgical treatment before you can tell how well it is working. Nonsurgical treatment typically includes:

Activity modification. You must make some changes in your lifestyle and avoid activities that aggravate your symptoms.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication. Drugs like aspirin and ibuprofen reduce pain and swelling.

Physical therapy. Strengthening shoulder muscles and working on shoulder control can increase stability. Your therapist will design a home exercise program for your shoulder.

Surgical Treatment

Surgery is often necessary to repair torn or stretched ligaments so that they are better able to hold the shoulder joint in place.

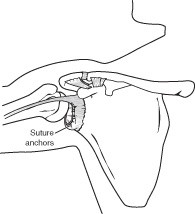

Bankart lesions can be surgically repaired. Sutures and anchors are used to reattach the ligament to the bone.

Arthroscopy. Soft tissues in the shoulder can be repaired using tiny instruments and small incisions. This is a same-day or outpatient procedure. Arthroscopy is a minimally invasive surgery. Your surgeon will look inside the shoulder with a tiny camera and perform the surgery with special pencil-thin instruments.

Open Surgery. Some patients may need an open surgical procedure. This involves making a larger incision over the shoulder and performing the repair under direct visualization.

Rehabilitation. After surgery, your shoulder may be immobilized temporarily with a sling.

When the sling is removed, exercises to rehabilitate the ligaments will be started. These will improve the range of motion in your shoulder and prevent scarring as the ligaments heal. Exercises to strengthen your shoulder will gradually be added to your rehabilitation plan.

Rotator Cuff Tears

A rotator cuff tear is a common cause of pain and disability among adults.

A torn rotator cuff will weaken your shoulder. This means that many daily activities, like combing your hair or getting dressed, may become painful and difficult to do.

Anatomy

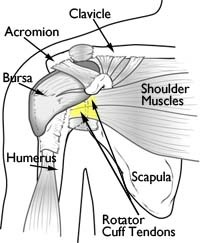

Your shoulder is made up of three bones: your upper arm bone (humerus), your shoulder blade (scapula), and your collarbone (clavicle). The shoulder is a ball-and-socket joint: The ball, or head, of your upper arm bone fits into a shallow socket in your shoulder blade.

Normal anatomy of the shoulder.

Your arm is kept in your shoulder socket by your rotator cuff. The rotator cuff is a network of four muscles that come together as tendons to form a covering around the head of the humerus. The rotator cuff attaches the humerus to the shoulder blade and helps to lift and rotate your arm.

There is a lubricating sac called a bursa between the rotator cuff and the bone on top of your shoulder (acromion). The bursa allows the rotator cuff tendons to glide freely when you move your arm. When the rotator cuff tendons are injured or damaged, this bursa can also become inflamed and painful.

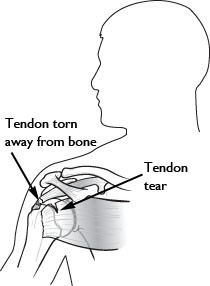

Description

When one or more of the rotator cuff tendons is torn, the tendon no longer fully attaches to the head of the humerus. Most tears occur in the supraspinatus muscle and tendon, but other parts of the rotator cuff may also be involved.

In many cases, torn tendons begin by fraying. As the damage progresses, the tendon can completely tear, sometimes with lifting a heavy object.

There are different types of tears.

- Partial Tear. This type of tear damages the soft tissue, but does not completely sever it.

- Full-Thickness Tear. This type of tear is also called a complete tear. It splits the soft tissue into two pieces. In many cases, tendons tear off where they attach to the head of the humerus. With a full-thickness tear, there is basically a hole in the tendon.

A rotator cuff tear most often occurs within the tendon.

Cause

There are two main causes of rotator cuff tears: injury and degeneration.

Acute Tear

If you fall down on your outstretched arm or lift something too heavy with a jerking motion, you can tear your rotator cuff. This type of tear can occur with other shoulder injuries, such as a broken collarbone or dislocated shoulder.

Degenerative Tear

Most tears are the result of a wearing down of the tendon that occurs slowly over time. This degeneration naturally occurs as we age. Rotator cuff tears are more common in the dominant arm. If you have a degenerative tear in one shoulder, there is a greater risk for a rotator cuff tear in the opposite shoulder — even if you have no pain in that shoulder.

Several factors contribute to degenerative, or chronic, rotator cuff tears.

- Repetitive stress.Repeating the same shoulder motions again and again can stress your rotator cuff muscles and tendons. Baseball, tennis, rowing, and weightlifting are examples of sports activities that can put you at risk for overuse tears. Many jobs and routine chores can cause overuse tears, as well.

- Lack of blood supply.As we get older, the blood supply in our rotator cuff tendons lessens. Without a good blood supply, the body’s natural ability to repair tendon damage is impaired. This can ultimately lead to a tendon tear.

- Bone spurs.As we age, bone spurs (bone overgrowth) often develop on the underside of the acromion bone. When we lift our arms, the spurs rub on the rotator cuff tendon. This condition is called shoulder impingement, and over time will weaken the tendon and make it more likely to tear.

Risk Factors

Because most rotator cuff tears are largely caused by the normal wear and tear that goes along with aging, people over 40 are at greater risk.

People who do repetitive lifting or overhead activities are also at risk for rotator cuff tears. Athletes are especially vulnerable to overuse tears, particularly tennis players and baseball pitchers. Painters, carpenters, and others who do overhead work also have a greater chance for tears.

Although overuse tears caused by sports activity or overhead work also occur in younger people, most tears in young adults are caused by a traumatic injury, like a fall.

Symptoms

The most common symptoms of a rotator cuff tear include:

- Pain at rest and at night, particularly if lying on the affected shoulder

- Pain when lifting and lowering your arm or with specific movements

- Weakness when lifting or rotating your arm

- Crepitus or crackling sensation when moving your shoulder in certain positions

Tears that happen suddenly, such as from a fall, usually cause intense pain. There may be a snapping sensation and immediate weakness in your upper arm.

A rotator cuff injury can make it painful to lift your arm out to the side.

Tears that develop slowly due to overuse also cause pain and arm weakness. You may have pain in the shoulder when you lift your arm to the side, or pain that moves down your arm. At first, the pain may be mild and only present when lifting your arm over your head, such as reaching into a cupboard. Over-the-counter medication, such as aspirin or ibuprofen, may relieve the pain at first.

Over time, the pain may become more noticeable at rest, and no longer goes away with medications. You may have pain when you lie on the painful side at night. The pain and weakness in the shoulder may make routine activities such as combing your hair or reaching behind your back more difficult.

Doctor Examination

Medical History and Physical Examination

After discussing your symptoms and medical history, your doctor will examine your shoulder. He or she will check to see whether it is tender in any area or whether there is a deformity. To measure the range of motion of your shoulder, your doctor will have you move your arm in several different directions. He or she will also test your arm strength.

Your doctor will check for other problems with your shoulder joint. He or she may also examine your neck to make sure that the pain is not coming from a “pinched nerve,” and to rule out other conditions, such as arthritis.

Imaging Tests

Other tests which may help your doctor confirm your diagnosis include:

- X-rays.The first imaging tests performed are usually x-rays. Because x-rays do not show the soft tissues of your shoulder like the rotator cuff, plain x-rays of a shoulder with rotator cuff pain are usually normal or may show a small bone spur.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or ultrasound.These studies can better show soft tissues like the rotator cuff tendons. They can show the rotator cuff tear, as well as where the tear is located within the tendon and the size of the tear. An MRI can also give your doctor a better idea of how “old” or “new” a tear is because it can show the quality of the rotator cuff muscles.

Treatment

If you have a rotator cuff tear and you keep using it despite increasing pain, you may cause further damage. A rotator cuff tear can get larger over time.

Chronic shoulder and arm pain are good reasons to see your doctor. Early treatment can prevent your symptoms from getting worse. It will also get you back to your normal routine that much quicker.

The goal of any treatment is to reduce pain and restore function. There are several treatment options for a rotator cuff tear, and the best option is different for every person. In planning your treatment, your doctor will consider your age, activity level, general health, and the type of tear you have.

There is no evidence of better results from surgery performed near the time of injury versus later on. For this reason, many doctors first recommend nonsurgical management of rotator cuff tears.

Nonsurgical Treatment

In about 50% of patients, nonsurgical treatment relieves pain and improves function in the shoulder. Shoulder strength, however, does not usually improve without surgery.

Nonsurgical treatment options may include:

- Your doctor may suggest rest and and limiting overhead activities. He or she may also prescribe a sling to help protect your shoulder and keep it still.

- Activity modification.Avoid activities that cause shoulder pain.

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication.Drugs like ibuprofen and naproxen reduce pain and swelling.

- Strengthening exercises and physical therapy.Specific exercises will restore movement and strengthen your shoulder. Your exercise program will include stretches to improve flexibility and range of motion. Strengthening the muscles that support your shoulder can relieve pain and prevent further injury.

- Steroid injection.If rest, medications, and physical therapy do not relieve your pain, an injection of a local anesthetic and a cortisone preparation may be helpful. Cortisone is a very effective anti-inflammatory medicine.

The chief advantage of nonsurgical treatment is that it avoids the major risks of surgery, such as:

- Infection

- Permanent stiffness

- Anesthesia complications

- Sometimes lengthy recovery time

The disadvantages of nonsurgical treatment are:

- No improvements in strength

- Size of tear may increase over time

- Activities may need to be limited

Surgical Treatment

Your doctor may recommend surgery if your pain does not improve with nonsurgical methods. Continued pain is the main indication for surgery. If you are very active and use your arms for overhead work or sports, your doctor may also suggest surgery.

Other signs that surgery may be a good option for you include:

- Your symptoms have lasted 6 to 12 months

- You have a large tear (more than 3 cm)

- You have significant weakness and loss of function in your shoulder

- Your tear was caused by a recent, acute injury

Surgery to repair a torn rotator cuff most often involves re-attaching the tendon to the head of humerus (upper arm bone). There are a few options for repairing rotator cuff tears. Your orthopaedic surgeon will discuss with you the best procedure to meet your individual health needs.

Arthroscopy is a surgical procedure that gives doctors a clear view of the inside of a joint. This helps them diagnose and treat hip problems.

During hip arthroscopy, your surgeon inserts a small camera, called an arthroscope, into your hip joint. The camera displays pictures on a television screen, and your surgeon uses these images to guide miniature surgical instruments. This can be used to treat a number of hip conditions.

Hip arthroscopy has been performed for many years, but is not as common as knee or shoulder arthroscopy.

During arthroscopy, your surgeon can see the structures of your hip in great detail. (Right) Small instruments are used to repair a labral tear.

Anatomy

The hip is a ball-and-socket joint. The socket is formed by the acetabulum, which is part of the large pelvis bone. The ball is the femoral head, which is the upper end of the femur (thighbone).

A slippery tissue called articular cartilage covers the surface of the ball and the socket. It creates a smooth, frictionless surface that helps the bones glide easily across each other.

The acetabulum is ringed by strong fibrocartilage called the labrum. The labrum forms a gasket around the socket. This is thought to help form a fluid seal.

The joint is surrounded by bands of tissue called ligaments. They form a capsule that holds the joint together.

The under surface of the capsule is lined by a thin membrane called the synovium. It produces synovial fluid that lubricates the hip joint.

In a healthy hip, the femoral head fits perfectly into the acetabulum.

When Hip Arthroscopy Is Recommended

Your doctor may recommend hip arthroscopy if you have a painful condition that does not respond to nonsurgical treatment. Nonsurgical treatment includes rest, physical therapy, and medications or injections that can reduce inflammation. Inflammation is one of your body’s normal reactions to injury or disease. In an injured or diseased hip joint, inflammation causes swelling, pain, and stiffness.

Hip arthroscopy may relieve painful symptoms of many problems that damage the labrum, articular cartilage, or other soft tissues surrounding the joint. Although this damage can result from an injury, other orthopaedic conditions can lead to these problems, such as:

- Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) is a disorder where bone spurs (bone overgrowth) around the socket or the femoral head cause damage.

- Labral tear

- Dysplasia is a condition where the socket is abnormally shallow and makes the labrum more susceptible to tearing.

- Snapping hip syndromes cause a tendon to rub across the outside of the joint. This type of snapping or popping is often harmless and does not need treatment. In some cases, however, the tendon is damaged from the repeated rubbing.

- Synovitis causes the tissues that surround the joint to become inflamed.

- Loose bodies are fragments of bone or cartilage that become loose and move around within the joint.

- Hip joint infection

Planning for Surgery

If you are having arthroscopy, you will need a physical examination from a physician to assess your health. He or she will identify any problems that may interfere with the surgery.

If you have certain health risks, a more extensive evaluation may be necessary before your surgery. Be sure to inform your orthopaedic surgeon of any medications or supplements that you take. He or she may tell you which medications to stop and which to take prior to surgery.

If you are generally healthy, your hip arthroscopy will most likely be performed as an outpatient. This means you will not need to stay overnight at the hospital.

The hospital or surgery centre will contact you ahead of time to provide specific details of your procedure. Make sure to follow the instructions on when to arrive and especially on when to stop eating or drinking prior to your procedure.

You will be asked to fill in a number of questionnaires which will be submitted to a national data base. You will be asked to participate in this registry post-operatively filling in the same questionnaires at certain times after your surgery (https://www.britishhipsociety.com/main?page=NAHR)

Before the operation, you will also be evaluated by a member of the anaesthesia team. Hip arthroscopy is most commonly performed under general anaesthesia, where you go to sleep for the operation. You will be asked to complete pre-operative questionnaires relating to your hip function and pain. You will be invited to participate in The Non-arthroplasty Hip Registry, a nation-wide registry evaluating the outcome of hip surgery.

Surgical Procedure

At the start of the procedure, your leg will be put in traction. This means that your hip will be pulled away from the socket enough for your surgeon to insert instruments, see the entire joint, and perform the treatments needed.

After traction is applied, your surgeon will make a small puncture in your hip (about the size of a buttonhole) for the arthroscope. Through the arthroscope, he or she can view the inside of your hip and identify damage.

(Left) Your surgeon inserts the arthroscope through a small incision about 1-1.5cm. (Right) Other instruments are inserted to treat the problem. You may have up to 3 incisions in total

Your surgeon will insert other instruments through separate incisions to treat the problem. A range of procedures can be done, depending on your needs. For example, your surgeon can:

- Smooth off torn cartilage or repair it

- Trim bone spurs caused by FAI

- Remove inflamed synovial tissue

The length of the procedure will depend on what your surgeon finds and the amount of work to be done. If adequate clearance of bone cannot be achieved through the keyhole technique a small incision (5-8cm) may be used to open the joint.

Complications

Complications from hip arthroscopy are uncommon. Any surgery in the hip joint carries a small risk of injury to the surrounding nerves or vessels, or the joint itself. The traction needed for the procedure can stretch nerves and cause numbness in the perineal region (groin), but this is usually temporary.

There are also small risks of infection, as well as blood clots forming in the legs (deep vein thrombosis).

Recovery

After surgery, you will stay in the recovery room for 1 to 2 hours before being discharged to the ward. You usually stay in hospital overnight although this is not mandatory. You can also expect to be on crutches, for some period of time depending on the procedure performed (usually 4 weeks).

Rehabilitation

Your surgeon will develop a rehabilitation plan based on the surgical procedures you required. In some cases, crutches are necessary, but only until any limping has stopped. If you required a more extensive procedure, however, you may need crutches for 1 to 2 months.

In most cases, physical therapy is necessary to achieve the best recovery. Specific exercises to restore your strength and mobility are important. Your therapist can also guide you with additional do’s and don’ts during your rehabilitation.

Long-Term Outcomes

Many people (70 – 80%) return to full, unrestricted activities after arthroscopy. Your recovery will depend on the type of damage that was present in your hip.

For some people, lifestyle changes are necessary to protect the joint. An example might be changing from high impact exercise (such as running) to lower impact activities (such as swimming or cycling). These are decisions you will make with the guidance of your surgeon.

Sometimes, the damage can be severe enough that it cannot be completely reversed and the procedure may not be successful.

Trochanteric Bursitis

What is the trochanteric bursa?

In many areas of the body, muscles and tendons must slide over and against one another during movement. At each of these places, a small sac of lubricating fluid helps the muscles and tendons move properly. One of these places is the hip. Usually these sacs of fluid, called bursa function to reduce friction. The hip bone is one such area in the body.

What is trochanteric (hip) bursitis?

Trochanteric bursitis is a common problem that causes pain in the area of the hip over the bump that forms the greater trochanter. Eventually the pain may radiate down the outside of the thigh. When the bursa sac becomes inflamed, pain results each time the tendon has to move over the bone. The pain may eventually be present at rest and may even cause a problem sleeping.

What causes trochanteric (hip) bursitis?

Most cases of trochanteric (hip) bursitis appear gradually with no obvious underlying injury or cause. Trochanteric (hip) bursitis may occur after hip surgery. A fall on the hip may also injure the bursa.

How is trochanteric (hip) bursitis diagnosed?

The diagnosis begins with a history and physical examination. In fact, this is usually all that is necessary to make the diagnosis.

Treatment of trochanteric bursitis.

Treatment usually consists of the following:

- Use of heat & ice – 1 min alternate for half an hour every evening

- Use of regular NSAIDs

- Pilates and core strengthening exercises – physiotherapy

- Ultrasound guided steroid injection

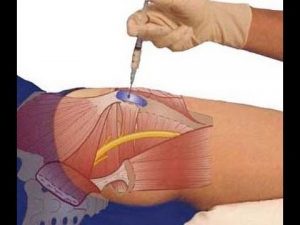

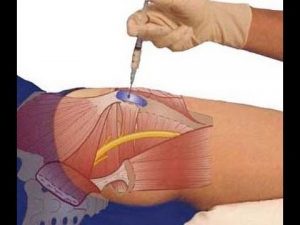

Procedure – Trochanteric Bursa Injection

How is this injection performed?

If your doctor uses ultrasound guidance, the nurse will position you on your side. Occasionally your doctor may perform the procedure without the use of ultrasound.

Your doctor will clean the area to be injected with an antibacterial solution. They will guide the needle to the greater trochanter. When they are satisfied with the needle placement, he will inject the medication into the area and remove the needle.

The nurse will clean the antibacterial solution off your skin and apply a dressing if needed.

I you require a sports hernia repair you will be referred to one of our trusted colleagues who specialise in this type of surgery.

Knee Arthroscopy

Knee arthroscopy is a surgical procedure that allows doctors to view the knee joint without making a large incision (cut) through the skin and other soft tissues. Arthroscopy is used to diagnose and treat a wide range of knee problems.

During knee arthroscopy, your surgeon inserts a small camera, called an arthroscope, into your knee joint. The camera displays pictures on a video monitor, and your surgeon uses these images to guide miniature surgical instruments.

Because the arthroscope and surgical instruments are thin, your surgeon can use very small incisions, rather than the larger incision needed for open surgery. This results in less pain for patients, less joint stiffness, and often shortens the time it takes to recover and return to favourite activities.

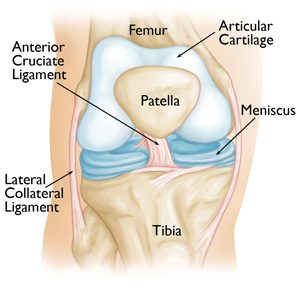

Anatomy

Your knee is the largest joint in your body and one of the most complex. The bones that make up the knee include the lower end of the femur (thighbone), the upper end of the tibia (shinbone), and the patella (kneecap).

Other important structures that make up the knee joint include:

- Articular cartilage. The ends of the femur and tibia, and the back of the patella are covered with articular cartilage. This slippery substance helps your knee bones glide smoothly across each other as you bend or straighten your leg.

- Synovium. The knee joint is surrounded by a thin lining called synovium. This lining releases a fluid that lubricates the cartilage and reduces friction during movement.

- Meniscus. Two wedge-shaped pieces of meniscal cartilage act as “shock absorbers” between your femur and tibia. Different from articular cartilage, the meniscus is tough and rubbery to help cushion and stabilize the joint.

- Ligaments. Bones are connected to other bones by ligaments. The four main ligaments in your knee act like strong ropes to hold the bones together and keep your knee stable.

- The two collateral ligaments are found on either side of your knee.

- The two cruciate ligaments are found inside your knee joint. They cross each other to form an “X” with the anterior cruciate ligament in front and the posterior cruciate ligament in back.

When is knee arthroscopy indicated?

Your doctor may recommend knee arthroscopy if you have a painful condition that does not respond to nonsurgical treatment. Nonsurgical treatment includes rest, physical therapy, and medications or injections that can reduce inflammation.

Knee arthroscopy may relieve painful symptoms of many problems that damage the cartilage surfaces and other soft tissues surrounding the joint.

Common arthroscopic procedures for the knee include:

- Removal or repair of a torn meniscus

- Reconstruction of a torn anterior cruciate ligament

- Removal of inflamed synovial tissue

- Trimming of damaged articular cartilage

- Removal of loose fragments of bone or cartilage

- Treatment of patella (kneecap) problems

- Knee sepsis (infection)

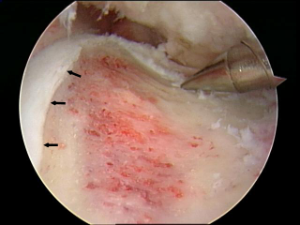

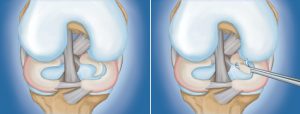

(Left) A large meniscal tear called a “flap” tear. (Right) Arthroscopic removal of the damaged meniscal tissue.

Positioning

Once you are moved into the operating room, you will be given anesthesia. To help prevent surgical site infection, the skin on your knee will be cleaned. Your leg will be covered with surgical draping that exposes the prepared incision site.

A tournique will be used to safely stop blood flow to the limb for the short period of your surgery.

Procedure

To begin the procedure, the surgeon will make a few small incisions, called “portals,” in your knee. A sterile solution will be used to fill the knee joint and rinse away any cloudy fluid. This helps your orthopaedic surgeon see the structures inside your knee clearly and in great detail

Closure

Most knee arthroscopy procedures last less than an hour. The length of the surgery will depend upon the findings and the treatment necessary.

Your surgeon may close each incision with a stitch or steri-strips (paper sutures), and then cover your knee with a soft bandage.

After simple arthroscopy, you are usually allowed to fully weight bear without the need for crutches. Your surgeon will advise you on this at the time of your surgery.

Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction

The knee is the most complex joint within the body. It depends on 4 major ligaments for stability. There are two ligaments either side of the knee: the medial collateral ligament and the lateral collateral ligament, and two crossed ligaments within the knee the posterior cruciate ligament and the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). The ACL runs through the centre of the knee from the back of the femur (thigh bone) to the front of the tibia (shin bone). The function of the ACL is in stabilising the knee especially in sidestepping, or pivoting. When the ACL is ruptured or torn the tibia moves abnormally such that the knee buckles or gives way.

Mechanism of Injury

The ACL is typically injured in a non-contact twisting movement involving rapid deceleration on the leg or a sudden changing of direction such as side stepping, or pivoting. The ACL can also be injured by a direct blow to the knee or hyperextension.

Injuries are associated with a popping sensation followed by the development of immediate swelling in the knee due to bleeding from the torn ligament. Depending on the exact mechanism of injury it is also possible to damage the cartilage within the knee or the other ligaments around the knee.

Rationale for treatment

Following a tear of the ACL your knee may have a tendency to give way when changing direction or pivoting. This can result in damage to the articular cartilage or the menisci of your knee.

Surgical reconstruction is therefore indicated in individuals who wish to return to pivoting type sports and in individuals who have problems with giving way during daily activities.

Aims of surgery

The aim of surgery is to prevent the repeated episodes of giving way of the knee. Published results indicate that approximately 90% of patients consider their knee to function normally or nearly normally after surgery. Full contact sport is allowed after rehabilitation but not everyone gets back to their previous level of sport. Other problems such as joint surface damage or meniscal tears may co-exist which can interfere with the joints ability to tolerate the high loads associated with sport. Wear and tear arthritis that is associated with ligament injury is not necessarily prevented by the reconstruction.

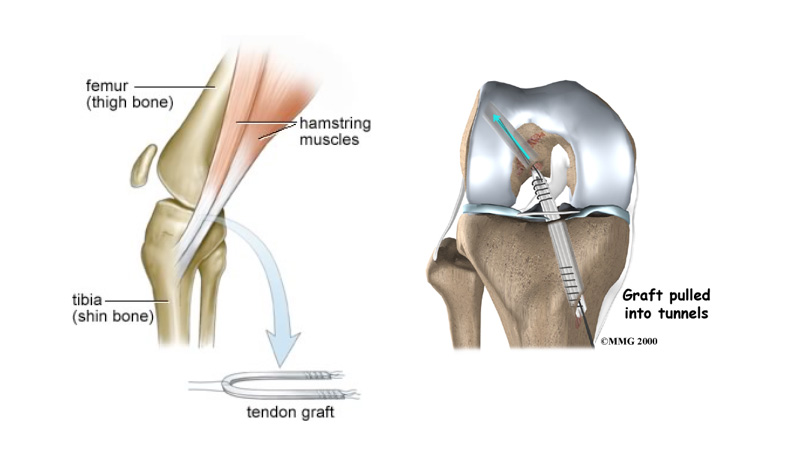

The operation

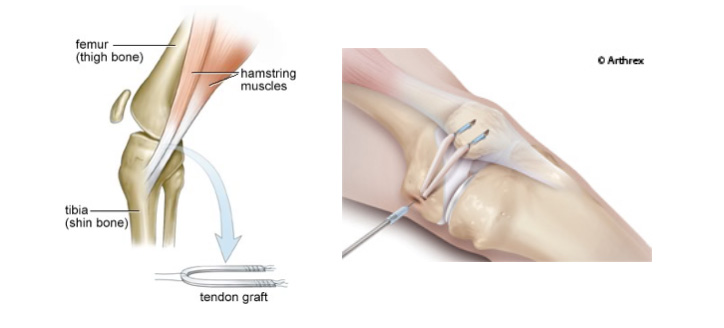

Reconstruction of the ACL usually involves replacing it with a hamstring graft.

Surgery is performed under general anaesthesia The hamstring tendons are harvested through a small incision on the tibia and then prepared into a new ligament. The inside of the knee is prepared using an arthroscopic (Key-hole) technique. Tunnels are made in the tibia and femur and the old ACL is removed to allow space for the new graft.

The new ligament is secured within the tunnels using screws. These usually do not need to be removed. If there is a tear of the meniscus (cartilage) then this is excised or repaired during the procedure.

What is involved for you as a patient?

Before the operation

Rehabilitation begins pre operatively to ensure that you and your knee are ready for the operation.

- Ensure full range of movement, especially being able to fully straighten the knee.

- Exercises to maintain quadriceps and hamstring muscle strength.

Operative Day

- Healthy patients are admitted on the day of surgery.

- You will be assessed by your surgeon and consented for surgery. This provides an opportunity for any further questions that you may have.

Post operative instructions

Your surgeon will visit you postoperatively and explain your surgery.

- Keep the wound dry for 7-10 days.

- Use of ice packs is recommended 10-15 mins x3 daily to relieve swelling.

- Analgesic (pain relieving) medication should be used as prescribed, particularly in the initial post-operative period

- Dissolvable sutures, deep to the skin, require no further attention. Occasionally nylon skin stitches may be required. These require removal 7-10 days post insertion at your local GP surgery. Paper stitches and adhesive dressings should be left in situ until they detach naturally.

Return to work

- Desk work at 7-10 days.

- Light manual work at approximately 6 weeks

- Heavy manual work (ladder work etc) at 3 – 4 months.

- Driving is permitted when you are able to walk comfortably and you are in safe control of your vehicle. This is typically at 3-4 weeks.

Rehabilitation

Physiotherapy is commenced immediately post-operatively.

There are five main rehabilitation phases

- Phase 1: Initial Post Op Phase (Range of movement excercises) – first 2 weeks

- Phase 2: Proprioception Phase – weeks 3 – 6

- Phase 3: Strength Phase – Weeks 6 – 12

- Phase 4: Early Sport Training (non-contact) – 6 months

- Phase 5: Return to Sport – 9 months

Risks of surgery

Graft failure

Re-rupture of the graft occurs in 5% of patients.

Continued instability

Failure to provide enough stability in the knee to allow return to full sporting activities. Either the ligament does not heal in a tight enough position to allow full confidence in the leg or there is associated damage inside the knee that prevents return to full function.

Infection

Surgery is carried out under strict germ free conditions in an operating theatre. Despite this infection occurs in 1 in 300 people. This may require further surgery and prolonged antibiotic treatment.

Clots in the leg (Deep venous thrombosis)

Although rare, this complication can be fatal if a clot travels to the lungs (Pulmonary embolism). Previous or family history of clots should be brought to the attention of the surgeon prior to your operation.

Numbness

Numbness at the side of the incisions can occur. This may be temporary or permanent.

Stiffness of the knee

Stiffening of the knee due to swelling causing difficulty in walking and pain on movement. Rarely some stiffness may be permanent.

Damage to structures around the knee

This is an extremely rare complication that can require further surgery.

Pain

The knee will be sore after the operation. Pain will improve with time. Rarely, pain will be a chronic problem and may be due to other complications listed above.

Medical complications

General complications

Following or during surgery there is risk of cardiac or respiratory complications. These risks are increased if you have current medical problems.

You must not proceed to surgery until you are confident that you understand this procedure, particularly the complications.

Medial Patellofemoral ligament (MPFL) reconstruction

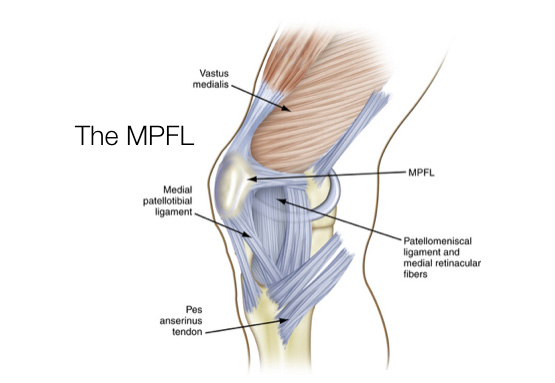

The medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL) helps to stabilise the patella (knee cap). The ligament attaches to the upper third of the patella and the inner aspect of the femur (thigh bone). It functions as a tether to stop sideways movement and dislocation of the patella.

The medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL) helps to stabilise the patella (knee cap). The ligament attaches to the upper third of the patella and the inner aspect of the femur (thigh bone). It functions as a tether to stop sideways movement and dislocation of the patella.

Following a patella dislocation the MPFL may become stretched and if symptoms of patella instability persist, a reconstruction of the ruptured ligament may be necessary.